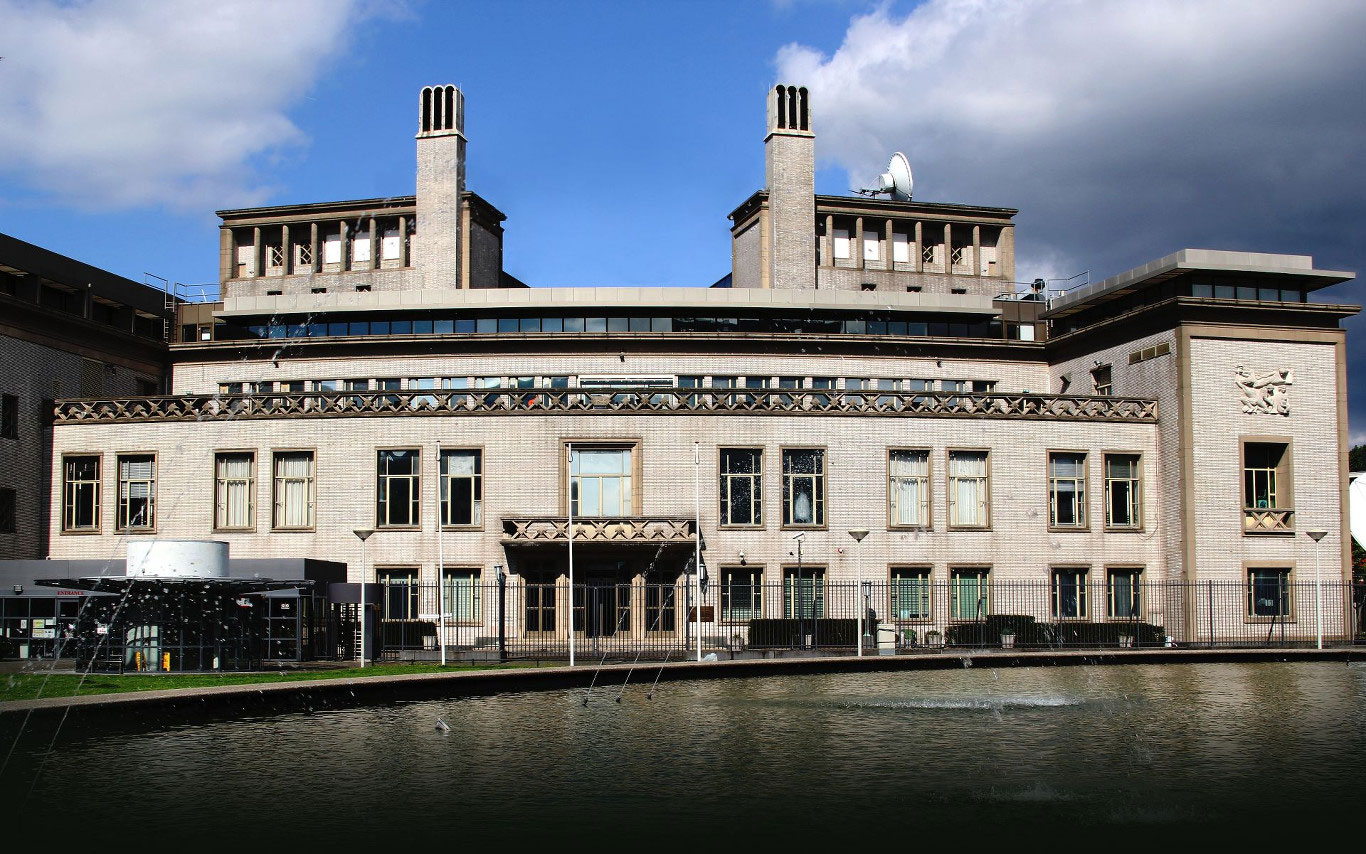

The Office of the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) has issued a total of 12 indictments against 18 political, military and police officials from Yugoslavia, Serbia and Croatia for crimes in the Republic of Croatia between 1991 and 1995.

In a total of five indictments, the Vukovar Three, Mile Mrkšić, Veselin Šljivančanin and Miroslav Radić, all Yugoslav People’s Army (JNA) military officers, were indicted for the Ovčara massacre. JNA General Pavle Strugar and Admiral Miodrag Jokić were charged with the shelling of the Old Town of Dubrovnik. Three presidents of the self-proclaimed Republic of Serbian Krajina in the occupied territory of Croatia, Milan Babić, Milan Martić and Goran Hadžić, were indicted for persecution and other grave crimes against Croats and other non-Serbs in Eastern Slavonia and the Knin Krajina.

All crimes in the five indictments: Ovčara and Dubrovnik, Škabrnja, Nadin, Lovas, Saborsko and other crime scenes in the occupied parts of Croatia, were also included in the indictment against then Serbian president, Slobodan Milošević. Those crimes committed by the police and volunteer units from Serbia were also alleged in indictments against the Serbian secret police chiefs, Jovica Stanišić and Franko Simatović, and against Serbian Radical Party leader, Vojislav Šešelj. Finally, the ICTY indicted General Momčilo Perišić for providing financial, personnel and logistical support to the Serbian Army of Krajina, alleging he had thus substantially contributed to the crimes committed by the Serbian troops, including the shelling of Zagreb in May 1995.

Croatian Army (HV) generals Mirko Norac and Rahim Ademi were indicted by the ICTY for the crimes against local Serbs in Gospić and in the Medak pocket; their cases were eventually referred to the Croatian courts. Generals Ante Gotovina, Ivan Čermak and Mladen Markač were brought to The Hague to face trial at the ICTY for the crimes committed during and after Operation Storm in the summer of 1995.

Of all the ICTY judgements rendered in cases of crimes in Croatia, the Operation Storm judgement is undoubtedly the most controversial. Generals Gotovina and Markač were unanimously convicted at trial and sentenced to 24 and 18 years in prison respectively, only to be acquitted on appeal by a three-two majority of Judges Meron, Güney and Robinson against Judges Pocar and Agius. In the two judgements - relying on the same facts and the same law - the Trial and Appeals Chambers judges came to diametrically opposite conclusions on key issues contested at the trial by both Prosecution and Defense.

The first controversial issue where the judges in the Trial Chamber and Appeals Chambers reached the opposite conclusions based on the same evidence relates to the the actual goal the political leadership in Croatia wanted to achieve when in August 1995 it planned and ordered the military and police operation codenamed Storm. This was the central issue for both parties in court and the main bone of contention between them.

The Prosecution never questioned the right of the Republic of Croatia to launch a military operation to reintegrate the Krajina territory and thus restore its internationally recognized borders: what they alleged was that the operation had another goal which was neither legitimate nor lawful: the permanent removal of the Serb population from those areas of Croatia which were first declared to be the Serbian Autonomous Region (SAO) of Krajina in 1991, and then became the Republic of Serbian Krajina. According to the indictment, the unlawful goal was achieved as part of a joint criminal enterprise which included, among other political, military and police officials the three accused generals - Gotovina, Čermak and Markač and was directed by the then Croatian president, Franjo Tuđman.

On the other hand, Defense insisted on Croatia's unalienable right to bring its territory back under its control after a four-year occupation which saw the local Croats terrorized and persecuted. According to the Defense, the Serb population left voluntarily, and the entire exodus was scripted and orchestrated by the authorities in the Republic of Serbian Krajina, and was not the result of a criminal enterprise whose goal was to permanently remove Serbs from Croatia.

The Goal of Operation Storm | Prosecution case

The Goal of Operation Storm | Teza obrane

Selection of Exhibits

Brioni meeting, 31 July 1995

Download transcript

Franjo Tuđman speech, 26 August 1995, Knin

Download transcript

Evacuation exercise, July 1995, TV Republic of Serbian Krajina

Download transcript

Savo Štrbac, 7 August 1995, Serbian TV, Banja Luka

Download transcript

Trial Chamber Conclusion

The Trial Chamber finds that members of the Croatian political and military leadership shared the common objective of the permanent removal of the Serb civilian population from the Krajina by force or threat of force, which amounted to and involved persecution, deportation, and forcible transfer.

The purpose of the joint criminal enterprise required that the number of Serbs remaining in the Krajina be reduced to minimum but not that the Serb civilian population be removed in its entirety.

The plan to drive the Serbs from Krajina was fine-tuned at the Brioni meeting with president Tuđman and the members of Croatian military and political leadership on 31 July 1995.

Tuđman's words from Brioni meeting "ostensibly guaranteeing them civil rights" pertain to Serb civilians and not Serb military forces. The aim was to leave for the civilians a way out.

The Trial Chamber finds that the references at the meeting to civilians being shown a way out was not about the protection of civilians but about civilians being forced out.

The leader of Krajina Serbs Milan Martić issued the evacuation order in the afternoon on 4 August 1995, at the time when a large number of people already left their homes. The order had no influence on their departure.

Appeals Chamber Conclusion

The Appeals Chamber with a majority of votes (judges Meron, Güney and Robinson) concludes that no reasonable Trial Chamber could establish that the only reasonable interpretation of the circumstantial evidence on the record was that a Joint Criminal Enterprise (JCE) with a common goal to permanently remove the Serb civilian population from the Krajina by force or threat of force existed.

The Majority’s conclusion quashing the existence of the JCE is based on an incorrect reading of the Trial judgement.

Dissenting Opinion of Judge Pocar

The Appeals Chamber with a majority of votes concludes that it was not reasonable to find that the only possible interpretation of the Brioni Transcript involved a JCE to forcibly deport Serb civilians.

The Majority appears quick to dismiss the evidence drawn from the Brioni Meeting.

Dissenting Opinion of Judge Agius

The Majority concludes that portions of the Brioni Transcript deemed incriminating by the Trial Chamber can be interpreted [...] as a lawful consensus on helping civilians temporarily depart from an area of conflict for reasons including legitimate military advantage and casualty reduction.

These suggestions are simply grotesque.

Dissenting Opinion of Judge Pocar

The Appeals Chamber didn't deal with plans and orders for evacuation of Serb civilian population.

The second contentious issue where the two Chambers, reached entirely opposing conclusions based on the same evidence concerns the purpose behind the shelling of Krajina towns as Operation Storm began, on 4 and 5 August 1995.

According to the Prosecution, the order issued by General Ante Gotovina on 2 August 1995 to 'open artillery fire on the towns' of Knin, Obrovac, Benkovac and Gračac, was evidence on its face of the clear intention of the participants in the joint criminal enterprise to target inhabited areas with indiscriminate fire, in order to cause panic among the people, to make them flee. This is precisely what happened.

The Defense argued there was no need for General Gotovina to specify military targets to be neutralized in a general order, since the subordinate commands did that upon receiving his orders. According to the Defense, the towns were shelled selectively: the artillery targeted military facilities and enemy firing positions. Any damage to civilian facilities and civilian casualties could be considered as collateral, which was not only acceptable, but in fact negligible.

The documents that might have shed additional light on the real purpose of the shelling of the towns in Krajina, the infamous parts of 'artillery diaries' produced by the Croatian Army, were never found.

The Purpose of Shelling | Prosecution case

The Purpose of Shelling | Defense case

Selection of Exhibits

Shelled areas in Knin, Prosecution evidence

Shelling of Knin, Defense evidence

UN Camp Blockadge, 5 August 1995

Download transcript

Trial Chamber Conclusion

Deportation of Serbs from Krajina occurred as a result of unlawful artillery attacks on civilians and civilian objects in the towns of Knin, Benkovac, Obrovac and Gračac. The Trial Chamber concluded these attacks were committed on discriminatory grounds and constitute part of the joint criminal enterprise.

The Trial Chamber carefully compared the evidence on the locations of impacts in these towns with the locations of possible military targets.

The Trial Chamber considers it a reasonable interpretation of the evidence that those artillery projectiles which impacted within a distance of 200 metres of an identified artillery target were deliberately fired at that military target.

Based on this comparison, and the relevant artillery orders and reports, the Chamber concluded that the Croatian forces deliberately targeted in these towns not only previously identified military targets, but also areas devoid of such military targets.

The Chamber thus found that the shelling of Knin, Benkovac, Obrovac and Gračac on 4 and 5 August 1995 constituted an indiscriminate attack on these towns and an unlawful attack on civilians and civilian objects.

The Trial Chamber finds that the unlawful attack against civilians and civilian objects was part of a widespread and systematic attack against a civilian population and it constitutes persecution as a crime against humanity.

Appeals Chamber Conclusion

The Appeals Chamber, judges Agius and Pocar dissenting, finds that the Trial Chamber erred in conclusion that the artillery attacks were unlawful. The departure of civilians from the towns and villages affected by the legitimate artillery attacks can't be characterized as deportation.

The Majority holds that the Trial Chamber’s errors with respect to the 200 Meter Standard and targets of opportunity are sufficiently serious that the conclusions of the Impact Analysis cannot be sustained.

Having found that the 200 Meter Standard was erroneous [...] the Appeals Chamber had [...], two obligations. First, to identify and articulate the correct legal standard and, second, to apply this standard to the evidence contained in the trial record [...].However, in contravention of our well-established appellate standard of review, the Majority followed neither of these requirements.

Dissenting Opinion of Judge Pocar

The Appeals Chamber with a majority of votes considers unfounded the 200 meter standard, and concluded that all the finding on unlawful shelling of the Krajina towns are incorrect.

The Majority inflates, beyond any reasonable proportion, the importance of the Trial Chamber’s so-called error in respect of the 200 Meter and uses that error to undermine the Trial Chamber’s Impact Analysis in what I consider to be a most artificial way.

Dissenting Opinion of Judge Agius

Neither party contested the fact that a certain number of people were murdered, some during Operation Storm, but most of them in its aftermath. All other allegations surrounding the murders, however, were at issue: the scope of the crimes, the status of victims and perpetrators, the motives for the killings and the attitude of both the accused and the Croatian judiciary towards the crimes and their perpetrators.

The Prosecution claimed that hundreds of Serbs, mostly civilians, were killed during and after Operation Storm, as were some soldiers who were hors de combat, i.e. who no longer took part in the fighting. Most of the victims were elderly men and women, some disabled, who could not or did not want to leave their homes. According to the Prosecution, these people were killed by Croatian soldiers and police officers, as campaign of persecution involving wide-spread and systematic attacks on civilians. Last but not least, the Prosecution alleged that the Accused, who were the superior officers to the perpetrators of the crimes, failed to take reasonable and necessary measures to prevent the crimes or punish the perpetrators. The Croatian military and civilian judiciary failed to investigate the crimes in order to identify and prosecute the perpetrators.

The Defense challenged all those allegations, starting with the number and status of victims. Claiming that the average age of soldiers serving in the Serbian Army of Krajina was quite high, the Defense argued that many of the men in their sixties or seventies who were killed may well have been soldiers, not civilians. They also asserted that the murders might have been perpetrated by civilians wearing military uniforms. In most cases, the Defense claimed that the murders were tied to looting: the motive was clearly financial gain, not a desire to expel Serbs. Finally, the Defense contended that the Prosecution had failed to prove that the Accused Generals knew about the crimes committed by their subordinates yet failed to do anything to prevent crimes or punish the perpetrators. According to the Defense, it was patently untrue that the Croatian judiciary had turned a blind eye to the crimes against Serbs.

Most of the evidence presented by the parties focused on the murders in the Krajina village of Grubori, where on 25 August 1995, five elderly Serbs were killed.

The Prosecution argued that the Serbs were murdered by the Croatian special police and that there were subsequent attempts to cover up the crime, ordered from the very top, with the collusion of the two of the three generals, in this case Markač and Čermak. The Prosecution led evidence that the initial reports about the Grubori incident had been doctored; a description of the alleged firefight with the 'Chetnik' stragglers in which five elderly Serbs were killed was added to the report at a later date.

In principle, the Defense did not deny that these crimes happened, but asserted that their clients were victims of the report doctoring and that they were not the ones who altered the documents.

Murders | Prosecution case

Murders | Defense case

Selection of Exhibits

Interview with residents of Grubori, August 1995, UNTV

Download transcript

Ivan Čermak in Grubori, 27 August 1995, Croatian Radio-television

Download transcript

Burned houses in Grubori, August 1995, UNTV

Interview with villagers from Knin area, August 1995, UNTV

Download transcript

Trial Chamber Conclusion

The Trial Chamber found that members of the Croatian military forces and Special Police committed a large number of murders, charged as war crimes and crimes against humanity.

Crimes, including murder, destruction, plunder, and inhumane acts, committed by members of Croatian military forces and Special Police caused duress and fear of violence and added to the creation of an environment in which these persons had no choice but to leave.

Considering the large number of crimes committed in a relatively short period of time, the Chamber found that there was a widespread and systematic attack directed against this Serb civilian population.

On 25 August 1995, members of the Special Police murdered several elderly villagers in the hamlet of Grubori. The accused Markač participated in the cover-up of crimes by creating a climate of impunity which encouraged the commission of crimes against Krajina Serb persons and property.

Appeals Chamber Conclusion

The Appeals Chamber, judges Agius and Pocar dissenting, finds that absent the finding of unlawful artillery attacks and resulting displacement, the Trial Chamber’s conclusion that the common purpose crimes of deportation, forcible transfer, and related persecution, including murders, took place cannot be sustained.

The conclusion on the existence of the joint criminal enterprise did not rest solely on the existence of unlawful artillery attacks but is based on three other groups of evidence: 1. the Brioni Meeting and the preparation of Operation Storm, 2. the crimes committed by the Croatian military forces and Special Police including murders against the remaining Serb civilian population and 3.prevention of the return of Serb refugees.

Dissenting Opinion of Judge Pocar

Quashing the Trial Chamber's findings on unlawful shelling and joint criminal enterprise, The Majority in the Appeals Chamber didn't deal with other elements of the first instance judgement that led to conviction.

The Appeals Chamber’s Majority didn't deal with other elements of the first instance judgement that led to conviction.

The Majority concludes that the findings on Markac's responsibility were made in the context of the findings on the unlawful nature of the artillery attacks. Quashing the findings on the existence of the unlawful artillery attacks, the majority in Appeals Chamber quashed the findings on the responsibility of the accused on all the other counts.

Again, neither the Prosecution nor the Defense contested that in the aftermath of the military and police operation Storm, a wave of destruction, looting and burning of Serb property swept the Krajina. While this fact was not controversial, everything else was: the scale of the destruction; the motive behind it; the status of the perpetrators and the attitude of the Croatian civilian and military institutions towards the incidents.

According to the Prosecution, by November 1995 a total of 17,200 out of 22,313 Serb houses were completely or partially destroyed, burned and looted in the post-Storm wave of systematic destruction. The Defense asserted this to be 'a flood of harmful events' that inevitably follows in the wake of all major military operations.

Defense claimed the crimes were committed by 'individuals' who 'acted independently'. Their motive for arson was revenge, and as for looting, they were motivated by profit. While the Prosecution did not contest that this may well have been the motive of the direct perpetrators, it argued that the participants in the joint criminal enterprise did have an additional motive: to make the remaining Serbs leave their homes in the Krajina and to prevent the return of those who had already left. This is why they let loose their troops and tolerated their criminal conduct, so long as it served the purpose of the joint criminal enterprise.

These allegations were challenged by the Defense, noting that the highest ranking political and military officials in Croatia, Tuđman, Šušak, Červenko and others, issued a number of instructions in the aftermath of Operation Storm strictly prohibiting any 'undisciplined behavior' and ordered that 'law and order' be imposed in the Krajina to prevent any further arson and looting.

The Prosecution responded that those instructions were 'general' and 'lacked bite'. They were issued to whitewash the true intentions of the Croatian authorities, to create an impression that they wanted to prevent arson and looting. The real purpose of the instructions and orders was to evade responsibility for the failure to prevent crimes and punish the perpetrators. Those who issued them knew full well the documents would not put a stop to the crimes.

Destruction and Plunder of Property | Prosecution case

Destruction and Plunder of Property | Defense case

Selection of Exhibits

Burned villages near Knin, 13 August 1995, UNTV

Franjo Tuđman and Elisabeth Rehn meeting, 4 November 1995

Download transcript

Trial Chamber Conclusion

The Trial Chamber recalls its findings on wanton destruction and destruction of property which was owned or inhabited by Krajina Serbs. Based on this, the Trial Chamber finds that the acts of destruction and burning of private property was discriminatory in fact. The findings also include that the destruction took place on a large scale. Based on this, the Trial Chamber finds that the destruction had a severe impact on the victims.

The Trial Chamber considered in particular that in some instances acts of plunder were carried out simultaneously and by the same persons as acts of destruction. The Trial Chamber also considered that in other incidents members of Croatian military forces and civilians were plundering together, or at least at the same time and the same place and that in many instances items were taken from many houses.The Trial Chamber finds that their appropriation was unlawful.

Therefore, the Trial Chamber finds that the incidents constitute plunder as violations of the laws or customs of war.

Considering circumstances such as the ethnicity of the victims and the time and place where the acts took place, the Trial Chamber finds that the plunder and looting was part of a widespread and systematic attack against a civilian population.

In conclusion, the Trial Chamber finds that the plunder and looting constitutes persecution as a crime against humanity.

Appeals Chamber Conclusion

Quashing the Trial Chamber's findings on unlawful shelling and joint criminal enterprise, the Majority didn't deal with other elements of the first instance judgement that led to conviction.

The existence of the JCE as defined by the Trial Chamber did not rest solely on the existence of unlawful artillery attacks but was instead based on four mutually reinforcing sets of events including the crimes committed by the Croatian military forces and Special Police against the remaining Serb civilian population and property after 5 August 1995.

Dissenting Opinion of Judge Pocar

The destruction of the abandoned Serb houses was not the only tool the participants in the joint criminal enterprise had at their disposal. According to the Prosecution, they tried to prevent the return of the Serb refugees by passing administrative and bureaucratic measures designed to cement the gains of Operation Storm: a territory without Serbs.

The Defense maintained that Croatia was not to blame for the Serbs' exodus: they were evacuated in accordance with the plans and orders of the Krajina leadership. Moreover, they argued that international law did not oblige Croatia to facilitate their speedy and unconditional return.

The Prosecution identified two mechanisms used to prevent the return of Serb refugees. The first consisted of administrative measures prohibiting all persons without valid Croatian identity papers from crossing into Croatia. The vast majority of Krajina Serbs did not have the Croatian documents. Furthermore, in the immediate aftermath of Storm, the government passed a decree stipulating that all Serbs who failed to return within 30 days would have their property seized and placed at the disposal of the state.

The second mechanism to prevent Serbs from returning was a Croatian ban on even those persons who had identity papers from entering Croatia and colonizing Krajina, i.e. settling Croats into abandoned Serb houses.

The Defense meanwhile argued that the Croatian state could not allow the Serb refugees to return en masse until relations between Croatia and the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (FRY), and later Serbia, were normalized. They invoked international law provisions stipulating that the authorities were not obliged to allow the return of those Serbs who left Croatia voluntarily to join Croatia's enemies: the FRY, Serbia or Republika Srpska.

Although Tuđman himself spoke about 'the colonization of Krajina', the Defense maintained that a state cannot 'colonize' its own sovereign territory, saying that the drive to settle Croats into abandoned Serb houses served to protect the property of Serb refugees from arson and looting and to ease the financial burden of caring for about 380,000 refugees and internally displaced persons who were housed in the hotels along the Adriatic coast.

Preventing the Return | Prosecution case

Preventing the Return | Defense case

Selection of Exhibits

Trial Chamber Conclusion

Immediately following the forcing out of the Krajina Serbs, members of the Croatian leadership took various measures, on a policy and legislative level, aimed at preventing them from returning. The intention was to ensure that the removal of the Krajina Serb population became permanent.

The Trial Chamber finds that the joint criminal enterprise also amounted to, or involved, imposition of restrictive and discriminatory measures as the crime against humanity of persecution.

The Chamber found that the motive underlying these legal instruments, as well as their overall effect, was to provide the property left behind by Krajina Serbs in the liberated areas to Croats, and thereby deprive these Serbs of the use of their housing and property.

The Chamber found that Franjo Tuđman, who was the main political and military leader in Croatia before, during, and after the Indictment period, was a key member of the joint criminal enterprise. Tuđman intended to repopulate the Krajina with Croats and ensured that his ideas in this respect were transformed into official policy.

The Chamber further found that other members of the joint criminal enterprise included Gojko Šušak, who was the Minister of Defense, Zvonimir Červenko, the Chief of the Croatian army Main Staff, and other members of the Croatian leadership.

Appeals Chamber Conclusion

The Appeals Chamber’s Majority holds that evidence of policy and legal attempts to prevent the return of Serb civilians who had left the Krajina is insufficient to justify the Trial Chamber’s view that a JCE to permanently remove Serb civilians by force or threat of force existed.

The Appeals Chamber’s Majority holds that the fact that Croatia adopted discriminatory measures after the departures of Serb civilians from the Krajina does not demonstrate that these departures were forced.

The Majority misinterprets the Trial Chamber’s findings, which did not rely on this discriminatory policy and property law to demonstrate that the departures were forced but rather found that they aimed at ensuring that the removal of the Krajina Serb population was permanent.

Dissenting Opinion of Judge Pocar

The majority holds that evidence of Tuđman’s speeches and of Croatian Army and Special Police crimes after the artillery assault on the Four Towns is insufficient to support the finding that a JCE existed.

In particular, it is unclear whether the goals and rhetoric of Tuđman’s speeches can be attributed to the JCE’s membership, or considered illustrative of its common purpose.

The only reasonable conclusion from the evidence was that there was a JCE whose common purpose was to permanently remove the Serb civilian population from the Krajina region by force or threat of force, which amounted to and involved the crimes of persecutions, deportation and forcible transfer.

Finally, even if the Majority wished to acquit Gotovina and Markač entirely, one might wonder what the Majority wanted to achieve by quashing the mere existence of the JCE rather than concentrating on Gotovina’s and Markač’s significant contributions to the JCE. I leave it as an open question.

Dissenting Opinion of Judge Pocar

The Trial Chamber, comprised of Judges Alphons Orie, Uldis Kinis and Elisabeth Gwaunza, rendered its judgement on 15 April 2011. In a unanimous decision, the Accused Ante Gotovina and Mladen Markač were found guilty of participation in a joint criminal enterprise which included persecution on political, religious and racial grounds, murders, inhumane acts, looting, wanton destruction and cruel treatment, qualified as crimes against humanity and violations of the laws and customs of war. Ante Gotovina was sentenced to 24 and Mladen Markač to 18 years in prison. The third accused, Ivan Čermak, was acquitted of all charges.

Before the judges began their deliberations, the court was in session for 303 days. A total of 145 witnesses were heard and about 4,800 exhibits were admitted into evidence. The judges took more than eight months to reach the verdict, and the judgement was almost 1,400 pages long.

On 16 November 2012, a majority of the Appeals Chamber comprised of Judge Theodor Meron (from the US), Judge Mehmet Güney (Turkey) and Patrick Robinson (Jamaica) reversed the Trial Chamber’s conclusions on unlawful shelling and on the existence of a joint criminal enterprise run by the Croatian leadership. Gotovina and Markač were thus acquitted. Judges Carmel Agius (from Malta) and Fausto Pocar (Italy) were in the minority. By the Tribunal’s standards, the Appellate proceedings were completed in record time. The judgement had only 54 pages, which is why it is known in the legal circles as the ‘magazine judgement’. The decision will be remembered for the unusually strong language of its dissent, unprecedented in the 20 years of the Tribunal's jurisprudence. All in all, in the opinion of the dissenting judges, the majority’s conclusions ‘contradict any sense of justice’.

Although the Appeals Chamber quashed the generals' convictions and reversed the findings of the Trial Chamber on two critical issues, it did not reverse the first-instance findings on the persecution of the Serbs in Krajina. The murders, inhumane acts, destruction and looting of private property suffered by Serb civilians in Krajina, as well as the Croatian effort to prevent the Serb refugees from returning are all adjudicated facts that remain untouched.

While ICTY Appellate decisions are final, the Storm Trial and Appeal judgements found their way to the International Court of Justice (ICJ), which adjudicates disputes between states. There, they were presented as evidence in the genocide suits by Croatia and Serbia against each other. More specifically, Serbia relied on the first-instance judgement in which Gotovina and Markač were convicted as evidence on which to argue that crimes committed during Operation Storm had reached the scale of genocide, while Croatia challenged those claims, invoking the second-instance judgement in which the Defendants were acquitted.

In its judgement issued in February 2015, the ICJ found that both the Serb and Croat forces had committed serious crimes between 1991 and 1995; some of those crimes containing the substantive elements of genocide. The intent, however, was not to ‘destroy’ an ethnic group but to ‘forcibly remove’ its members from specific parts of the territory.

As for the ICTY judgements on Operation Storm, the ICJ, in reaching its conclusion that killings during those shelling attacks did not constitute genocide gave weight to the findings of the Appeals Chamber that the shelling of the four Krajina towns had not been unlawful and that there had been no joint criminal enterprise. The ICJ Judges considered that the factual findings in the Trial Chamber Judgement about murders, cruel treatment, wanton destruction and looting of private and public property were “highly persuasive”, since they were not “upset on appeal”.

It is interesting to note here the ICJ’s conclusion that the Serb exodus was a foreseen, probable and desirable consequence of the planned military action:

"[...]The Court notes that it is not disputed that a substantial part of the Serb population of the Krajina fled that region as a direct consequence of the military actions carried out by Croatian forces during Operation “Storm”, in particular the shelling of the four towns [...] It further notes that the transcript of the Brioni meeting [...] makes it clear that the highest Croatian political and military authorities were well aware that Operation “Storm” would provoke a mass exodus of the Serb population; they even to some extent predicated their military planning on such an exodus, which they considered not only probable, but desirable. (ICJ judgement, paragraph 479)

In the twenty years since Operation Storm, the Croatian authorities have issued three indictments against seven Croatian soldiers and police officers for war crimes against the Krajina Serbs. One trial has resulted in a conviction, five accused were acquitted because of lack of evidence, while one trial is still ongoing.

Furthermore, a total of 6,390 criminal reports have been submitted to the various public prosecution offices concerning the crimes committed during and after Operation Storm. According to statistical data, as many as 2,380 have been convicted for petty crimes. While the total number of criminal reports includes 439 against army personnel, the names and crimes of those convicted have not been made public.